REMNANT TRUST COLLECTION

John Locke

“The end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom. For in all the states of created beings capable of law, where there is no law, there is no freedom.”

– Locke

b. 1632 CE – d. 1704 CE

John Locke, English philosopher, was born six years after the death of Bacon, and three months before the birth of Spinoza. In 1646, he entered Westminster School and remained there for six years. Westminster was uncongenial to him. Its memories perhaps encouraged the bias against public schools, which afterwards disturbed his philosophical calm in his Thoughts on Education. When Locke was young, he believed that what was called general freedom was general bondage, and that the popular assertors of liberty were the greatest engrossers of it too, and not unfitly called its keepers. John Locke was opposed to the doctrine that the king rules by divine right and that he has absolute power to govern men as he wills.

Locke held that the original and natural state of all men was one of perfect freedom and equality. Since all men are free and equal, no one has the right to take away another’s life, liberty, or possessions. The main purpose of law, Locke taught, is to preserve the social groups and thus it must be limited to the public good of society.

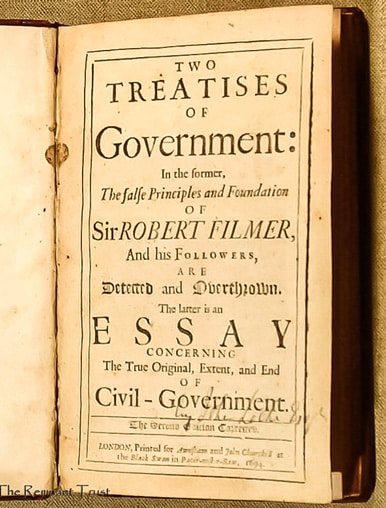

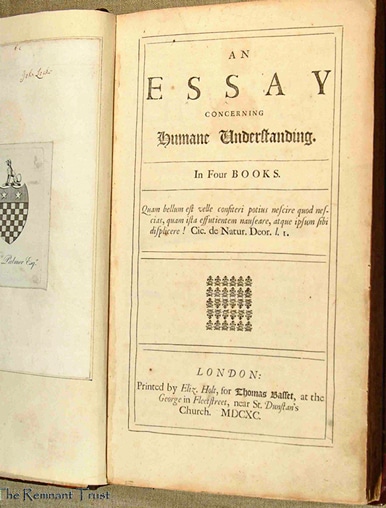

Beyond this, men are to be left free. After his death in 1704, when it was confirmed that the internationally renowned author of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding had also written the anonymously published Two Treatises of Government, Locke was widely taken to represent a distinctive type of political theory based on individual rights and the social contract.